Activist shown the door illegally? Open Door complaints vs. school boards piling up

“There has been a sharp uptick in disruptive and even dangerous public meetings"

MUNCIE — Insults were yelled, comparisons were made to Nazi Germany and a member of the audience got kicked out during a Sept. 14 meeting of the Muncie school board.

Chris Hiatt, the person who was removed, later filed a complaint with the state’s Public Access Counselor, Luke Britt, accusing the Muncie Community Schools board of trustees of violating his rights under the Open Door Law.

The complaint is just one of 42 filed against Indiana school boards this year with Britt’s office (23 of which remain under review).

COVID-19 issues, including masks and vaccinations, along with library books, critical race theory, educational equity, social-emotional learning, cultural awareness, and restorative justice practices are fueling the record number of complaints.

“There has been a sharp uptick in disruptive and even dangerous public meetings,” Seamus Boyce, an Indianapolis lawyer who represents schools, complained to Britt recently. “The personal attacks if continued could lead to an unprecedented wave of public servants leaving their professions.”

In response to Boyce’s appeal for guidance, Britt — an attorney first appointed as Public Access Counselor by Gov. Mike Pence — on Oct. 28 issued an “informal opinion” that concluded:

“It has indeed been disappointing to see the unrest at public meetings recently and it is past time to restore civility to the conversation.”

Britt’s office already has fielded more Open Door/Access to Public Records complaints against school boards this year than in 2019-20 combined, and this year isn’t over.

In an interview, Britt said, "I’ve never seen anything like this,” adding, “this one isn’t going away.”

“It’s going to get worse before it gets better,” Britt told me, alluding to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s recent authorization of the emergency use of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for the prevention of COVID-19 to include children ages 5 -11.

The access counselor thinks pandemic restrictions are making people “kind of stir crazy;” “they’re taking out their frustrations on the government;” and “certain political ideologies are amplifying certain issues, one being diversity, equity and inclusion.”

It appears to Britt that school boards are struggling with how to address these issues and how to communicate with frustrated parents. “I think being confronted with this caught schools a little flat-footed,” he said.

In one advisory opinion issued earlier this year, Britt concluded that Fremont Community Schools (Steuben County) violated the Open Door Law when the board went into an “emergency” executive session this past August to discuss the “quickly rising number of positive COVID cases among students and staff … “

The local newspaper complained after being denied entry, and Britt didn’t buy the board’s “emergency” argument.

“In early 2020, when local communities and the world were facing a significant number of unknowns as it related to the pandemic, emergency meetings were held to address changing conditions,” he wrote. "This office, however, was not aware of any emergency meetings taking place in executive session (even at that time). By August 2021, COVID-19 was not sneaking up on anyone.”

At an East Noble School Corp. board meeting, a member of the audience who refused to stop talking was escorted out by law enforcement.

The Open Door Law makes it clear that the public has a right to attend public meetings, but the law is also clear that school boards and other governing bodies are not generally required to take public comment.

And the right to attend is not absolute. It does not give an attendee the right to disrupt and obstruct meetings.

The East Noble board claimed that the attendee was abusive, disorderly and disruptive. Britt concluded that the person possibly was abusive, but that the scant information provided to his office by the board failed to carry its burden to justify depriving the attendee the ability to remain as an observer.

A Franklin Community Schools board meeting turned heated when several attendees refused to wear masks. The meeting was recessed. The board allegedly met in private, in violation of the Open Door Law, during the recess, before calling the session back to order, then adjourning because the unmasked contingent refused to comply.

The board, however, did not violate the Open Door Law, Britt determined, because only two board members had met privately, with the superintendent, an attorney and the security officer, during the recess. The other three board members, a majority, remained with the audience.

Carmel Clay Schools board did not violate the Open Door Law when it closed the doors to a meeting after a larger than expected crowd showed up, Britt ruled. Thirty three members of the public and the media were allowed in before the meeting room filled to capacity. At issue was whether a larger crowd should have been anticipated, resulting in a move to a larger venue. The access counselor found that any prejudice to the public was unintended and the situation was not systemic or ongoing.

The case against the Muncie school board remains pending, and the facts of that case are hotly disputed.

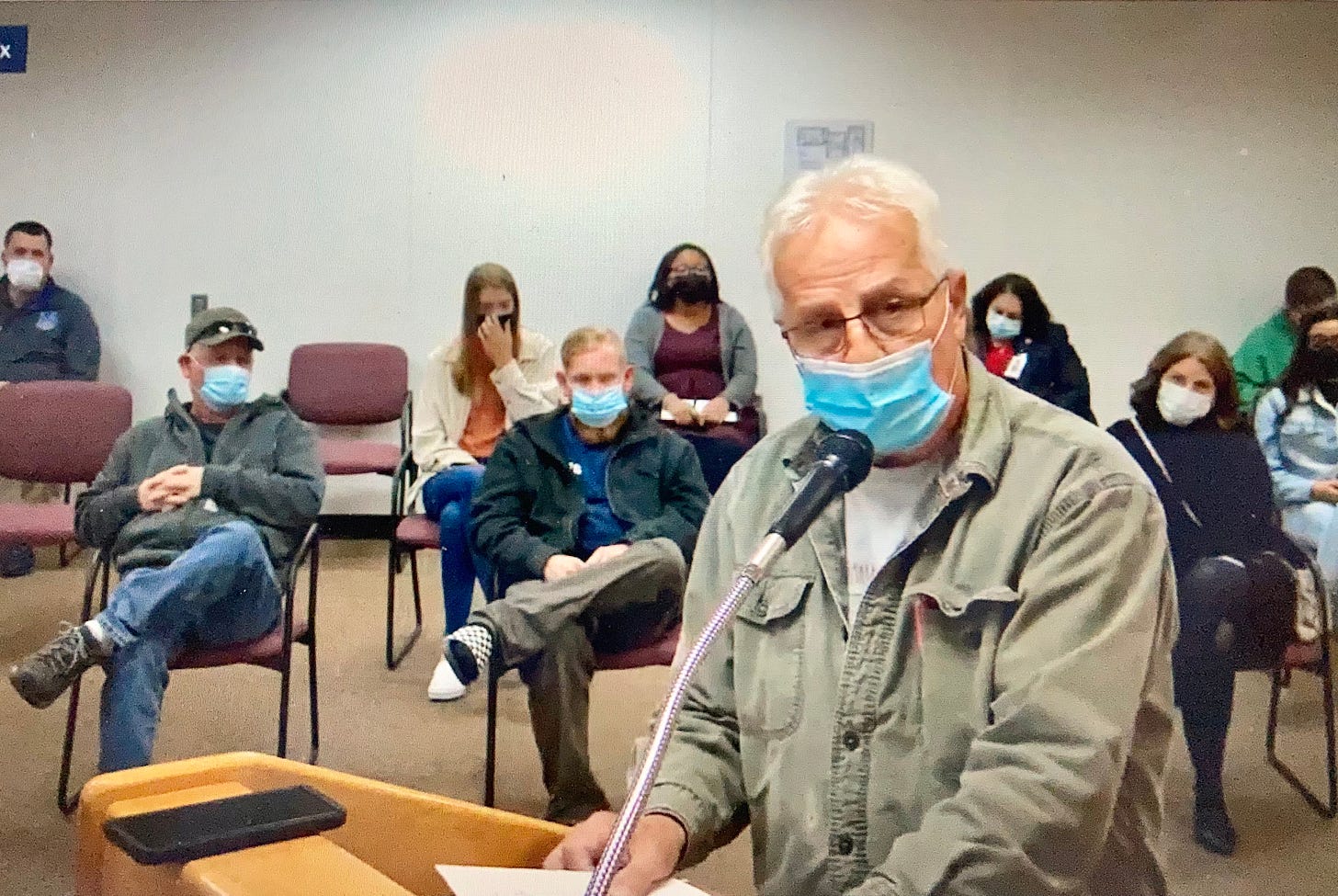

The complainant is Chris Hiatt, a small-business owner and longtime conservative activist who has locked horns with the government before.

At the meeting, Jim Williams, school board president, who happens to be an attorney and a former judge, noted that no one from the public had signed up to speak.

However, it became obvious that many attendees wanted to speak. But they were apparently unfamiliar with the board’s policy requiring those who want to do so to sign up on a sheet at the entrance before the meeting starts.

“When I stood up to address Mr. Williams and object to his effort to deny the public participation in the meeting, Mr. Williams had me ejected … without any explanation or defense as to why he had purposefully subverted public comment opportunity,” Hiatt wrote in a formal complaint to Britt.

In a response, school board attorney Alexander Pinegar, of Church, Church, Hittle + Antrim, Noblesville, reported that there were disturbances from the larger than normal audience even before the meeting started.

Some attendees reportedly yelled insults at the board after being required to either mask up or leave.

After Williams noted that no one from the audience had signed up to speak, many attendees became “visibly upset and disrupted the beginning of the meeting,” Pinegar wrote. “Comments were made comparing the situation to ‘communist China’ or ‘Nazi Germany.’

“Mr. Hiatt in particular stood up and began angrily complaining. The board president explained the public comment procedures. However, Mr. Hiatt complained even more loudly. The board president told Mr. Hiatt he would be escorted out if he did not stop disrupting the meeting. Mr. Hiatt did not stop. Instead, he became even louder.

“The board president then asked the School’s Chief School Resource Officer, Ray Dudley, to escort Mr. Hiatt out of the meeting. As Officer Dudley approached Mr. Hiatt, Mr. Hiatt said, ‘Come on Ray, be a man!’ to dissuade Officer Dudley from fulfilling his duties. Officer Dudley escorted Mr. Hiatt out of the meeting and a few others followed along, saying they would not stay if they could not speak.

“After Mr. Hiatt left, the room quieted and the meeting proceeded with no further disruption.”

Pinegar denies that the board violated the Open Door Law, on grounds that:

“Mr. Hiatt caused a disturbance. When asked to stop interfering with the meeting, he only persisted. The board president even warned Mr. Hiatt that he would be removed if he did not stop. When Mr. Hiatt did not comply, he was peacefully removed by the School’s Chief Resource Officer. At that point, if Mr. Hiatt wanted to observe the meeting, he was still able to via the live stream …

“ … the Open Door Law did not provide Mr. Hiatt a right to speak. It only provided Mr. Hiatt a right to observe the meeting. Mr. Hiatt’s own actions and intransigence caused the School to escort him out of the meeting, but even then, he was able to observe the meeting if he chose.”

(Before disallowing public comment, Williams did invite attendees to return, sign up and speak at a future meeting).

Meeting video disappears, backup missing audio

The school board attorney’s account might be a good defense for the board if it were true, but the facts are all wrong, Hiatt told me.

First of all, the school district’s YouTube video of the board meeting mysteriously is missing the entire time period described by Pinegar, including the exchange between Hiatt and Williams, Hiatt noted.

In response to an Access to Public Records request filed by Hiatt, the board did provide him a backup, seven-minute video of the controversial part of the meeting, but the audio, curiously, was not turned on, Hiatt went on. He quoted the school board as blaming the video recording mishaps on a stand-in, inexperienced videographer.

On the silent film, Hiatt notes, you can see Williams turn toward Hiatt — who is standing in the corner to Williams’ left — at the 5 minute, 48-second mark, when Hiatt begins speaking. At the 6 minute and two-second mark of the video, Williams is seen turning to his right and gesturing to Dudley, who crosses in front of the camera en route to escort Hiatt out.

In other words, “it was very brief, and there was no argument,” Hiatt said, adding that he remained “very calm and collected.”

In a written rebuttal submitted to Britt, Hiatt, who denies raising his voice at the meeting, asserts that Williams himself seemed “agitated and rather triggered” into becoming “boisterous and animated” at the outset of the meeting.

“I calmly inquired as to why Mr. Williams was so adamant about denying the citizen an opportunity to speak at the public comment period … My second comment was to what extent it would cause any harm under the circumstances to acknowledge those in attendance that wanted to speak and allow them to do so,” Hiatt told Britt.

Hiatt is also trying to learn the identities of the school board’s witnesses, and he maintains his story is backed by neutral witnesses.

He and others were able to speak at a subsequent board meeting for up to three minutes each.

In addition to other topics, Hiatt chose to talk about “school choice” in Indiana, which ensures among other things that every parent gets to choose the school where they send their child; what they’re being taught; and whether or not they have to “endure oppressive, abusive and unhealthy policies such as forcing your child to wear a mask for eight hours a day — and even more importantly to be rest assured that the minute they have authorization the Muncie Community Schools corporation will be undoubtedly mandating COVID vaccinations upon our children as well.”

Another speaker, Chris Hines, the parent of three Muncie school children, asked the board to answer “yes or no, is critical race theory being taught, because my daughter came home and told me you can’t be racist against white people because they have no culture.”

Williams assured Hines CRT is not part of the Muncie school curriculum

The board president’s opinion is that everyone should be focused primarily on addressing “the learning loss” “endured by these students at all levels” over the past 18 months, which has been “nothing short of drastic,” a “tragedy” and a crisis nationwide.

And it is “not our desire to keep kids in masks,” Williams said. “We hate it.” But masks were instrumental in keeping Muncie schools open, a unique accomplishment, he added.

Meanwhile, in his informal opinion on civility and public access, Britt says that “governing bodies can choose whether to extend the courtesy of a comment forum, and therefore revoke it if misused. Tumult, disorder, and disturbance on the part of the audience should not be tolerated by a board, council, or commission.

“This office does, and will always, advocate for a meaningful public comment opportunity at public meetings, if practical. Ultimately, however, a public comment forum during a meeting is a privilege and a courtesy extended by a governing body to the public.

“Various courts have recognized that reasonable rules, restrictions, and regulations can be placed on commenting, if the forum is opened. It is up to each governing body to set those policies and enforce them as objectively as possible.

“They can include … rules regarding time limits, keeping comments relevant to agenda and pending business items, and prohibition on malicious remarks. These types of measures should pass scrutiny so long as they are enforced consistently.”