No end in sight to state vs. farmers wetland disputes

A fight to the death? One of the parties already has died.

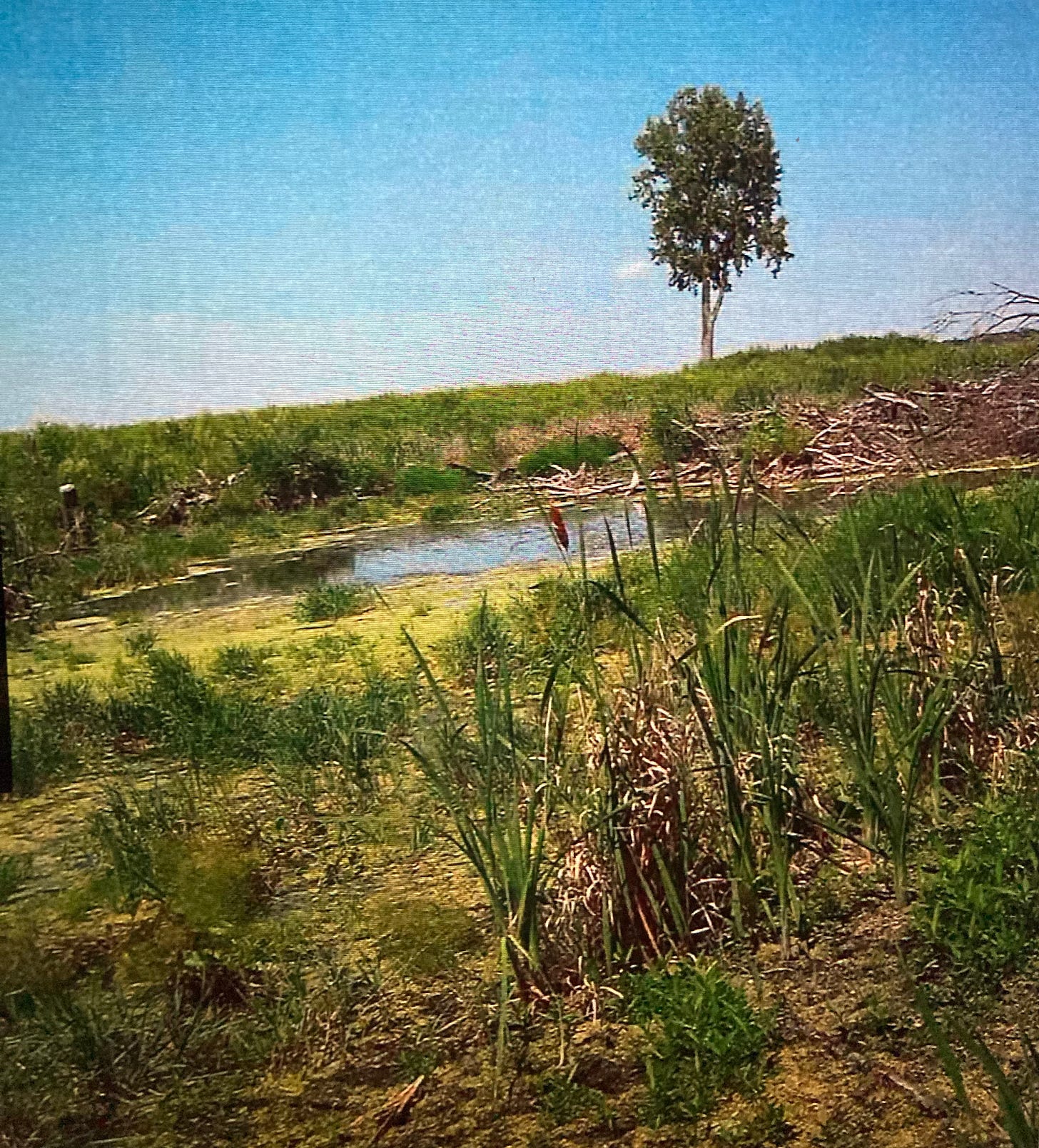

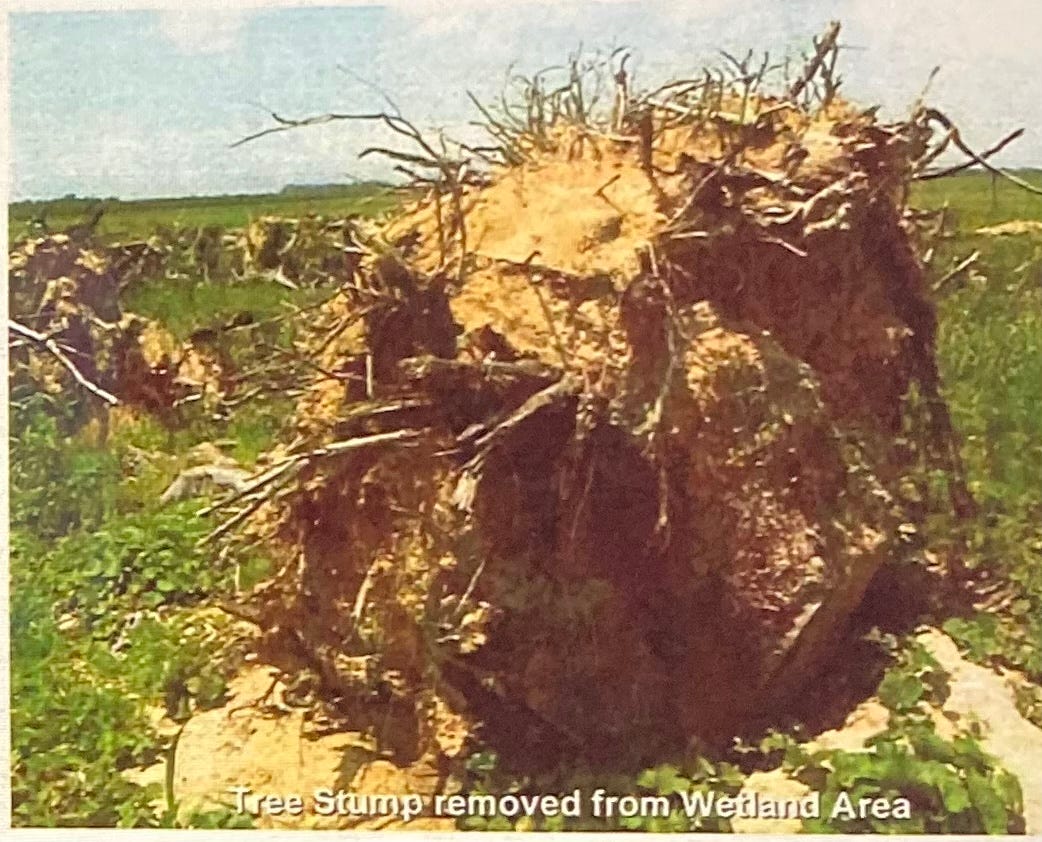

MUNCIE — Fifteen years ago, Larry Yeley bulldozed, burned and buried 12 acres of apparent forested wetlands in Delaware County, south of Yorktown, so he could farm it.

Likewise, seven years ago, Edwin Blinn Sr. mechanically cleared more than 20 acres of purported forested wetlands in Grant County, between Upland and Van Buren, also for farming purposes.

The two longtime growers — neither of whom had applied for the necessary state permits before destroying the alleged wetlands — have been stuck in costly legal battles with the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) ever since.

The agency continues to demand that the pair — both of whom own multiple fields across several counties — either restore the wetlands or create new ones elsewhere; IDEM is also seeking thousands of dollars in civil penalties.

In Yeley’s case, it’s starting to look like a fight to the death, I said to his attorney, who responded, “Exactly.”

The responsible party in that case is the Larry and Carol Yeley Family Limited Partnership. The couple are/were from McCordsville, in Hancock County (Carol Yeley died a year or so ago).

Summarizing a conference with attorneys representing IDEM and the Yeleys last September, Chief Environmental Law Judge Mary Davidsen wrote:

“The parties both noted harm from the length of time since alleged violations began, whether either was acting in bad faith or limiting consideration of Mr. Yeley's advanced age, health, and recent spousal death.”

Judge Davidsen will decide the Yeley case after a final, bench-trial-like hearing scheduled for Feb. 3-4. An earlier hearing was canceled after a party contracted COVID-19.

(Update: Just before publication of this article, the Yeley hearing reportedly was postponed again, until May 11-12, because of the current Omicron surge).

The judge already conducted a final evidentiary hearing in the Blinn matter, last year, but she is delaying her ruling in that one until after the Yeley hearing — to avoid having one case inadvertently serve as precedent for the other.

If either farmer loses, or if both lose, you can expect the dispute(s) to drag on longer, possibly for years, in the courts.

In an interview last year, Blinn told me he's prepared to fight to the Indiana Supreme Court, if necessary, to expose the state's "Gestapo" tactics, even though he could have bought another farm with all the money he's already spent on lawyers. He feels as though IDEM is treating his alleged wetland as though it were as important as Hoosier author Gene Stratton-Porter's Limberlost Swamp.

At the time I interviewed him, Blinn still had a highly visible semi-trailer parked near his home farm — along Ind. 18 between Interstate 69 and the city of Marion — plastered with a banner reading, "Trump 2020, From the Deplorables."

Blinn’s Republican allies in the state Legislature last year cited his ongoing legal woes with IDEM to help justify a controversial bill to repeal a state law regulating "isolated wetlands"— those not federally protected. It’s the law that required Blinn and Yeley to obtain permits from IDEM before adversely impacting wetlands.

However, the final version Gov. Eric Holcomb signed into law, SEA 389, ultimately preserved the program with some major modifications.

IDEM’s years-long enforcement actions against Blinn and Yeley remain under administrative review in the state’s Office of Environmental Adjudication (OEA), awaiting final rulings by Judge Davidsen, whose decisions can be appealed to trial courts through a process called judicial review.

“That’s the million-dollar question,” Yeley’s lawyer, Frank Deveau, told me when I asked whether SEA 389 was retroactive.

In the Yeley litigation, Judge Davidsen ruled: “The parties and Court discussed the most efficient method for obtaining a determination as to how Senate Enrolled Act (SEA) 389 affected this case. The parties agreed that the Court's ruling after evidentiary hearing may determine whether SEA 389 applied to this case.”

Representatives of IDEM and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources testified against SEA 389, warning that destruction of wetlands, sometimes known as nature’s sponges, would exacerbate flooding throughout the state. Wetlands also serve as rest stops for migratory birds; as habitat for plants and wildlife, including fish and fowl; bird-watching venues; as places to hunt and fish; as nature’s kidneys in trapping agricultural and other waste; and as storm water entry points that recharge groundwater supplies.

Indiana Farm Bureau and the Indiana Builders Association, representing the state’s home builders, testified in favor of the bill, whose 100 or so opponents included the Hoosier Environmental Council, The Nature Conservancy, Indiana Association of Soil and Water Conservation Districts, Ducks Unlimited, Quail Forever, Pheasants Forever, Indiana Native Plant Society, Indiana Wildlife Federation, League of Women Voters, Indiana Lakes Management Society, Indiana Sportsman’s Roundtable, Indiana Forest Alliance and Save the Dunes.

Deveau was not exaggerating when he referred to the million-dollar question.

It will cost both Yeley and Blinn seven figures if they are required to restore or replace the alleged wetlands, according to their attorneys.

“I feel bad about the cost to Mr. Yeley,” Deveau said. “He’s kind of painted into a box.” Regarding the possibility of a settlement, such as placing a conservation easement on Yeley’s controversial site or allowing it to lie fallow or idle, “IDEM won’t even talk about it; they won’t budge,” Deveau said.

“Because these matters are the subject of pending litigation, we cannot comment,” IDEM spokesman Barry Sneed responded.

In a legal brief in Blinn’s case, IDEM attorney Susanna Bingman said Blinn’s indignation over the regulatory costs mandated by the law to restore the wetlands destroyed by Blinn (or to create new ones) does not change the law.

And it is not IDEM that dictates how much it will cost Blinn to return the site to compliance; it's the law that does so, Bingman went on. If Blinn believes it will cost millions of dollars to restore or create new wetlands, he's in essence admitting he illegally destroyed a very large tract of wetlands, IDEM went on.

IDEM took law enforcement action in both cases after receiving complaints. Both sites continue to be farmed.

The state agency says in its legal filings that the size of the two wetlands in question remains undetermined. They could be smaller than believed to be, pending delineation.

After an IDEM inspector dug a shallow pit that found evidence of wetlands on Blinn’s property in the winter of 2015-16, he hired an attorney and an environmental consultant, Davey Resource Group, which conducted a wetland delineation to determine exactly how many acres of actual wetlands had been cleared, filled and impacted.

Davey indicated to IDEM that Blinn's initial intent was to do a wetland restoration project. But IDEM says its standard practice of informal resolution and multiple attempts at voluntary compliance proved unsuccessful in Blinn's case, resulting in the issuance of a notice of violation in May of 2018, followed by an IDEM commissioner's order six months later.

Later, however, Blinn won a protective order from Judge Davidsen allowing him to keep the wetland delineation report confidential.

IDEM suspected he didn't want to turn the report over "because Mr. Blinn was not happy with the delineation's findings." The agency said it had no reason to conduct the delineation itself because it was Blinn's responsibility and he had fulfilled it.

But the judge ruled Blinn had a right to invoke confidentiality because he had no plans to call the delineation report's author to testify — a ruling that the judge said could have affected the facts available and inferences to be made at the final hearing she held last year.

Acting on an anonymous complaint, state and federal inspectors in early 2016 found evidence of a forested wetland on Blinn’s property in addition to using a spade to dig a shallow pit, which quickly filled with water. Added evidence included personal observation of trees being cleared with heavy equipment; the presence of wetland plants like red twig dogwood shrubs, green ash tree saplings, and nodding beggarticks wildflower; and soil maps and aerial imagery of visible inundation.

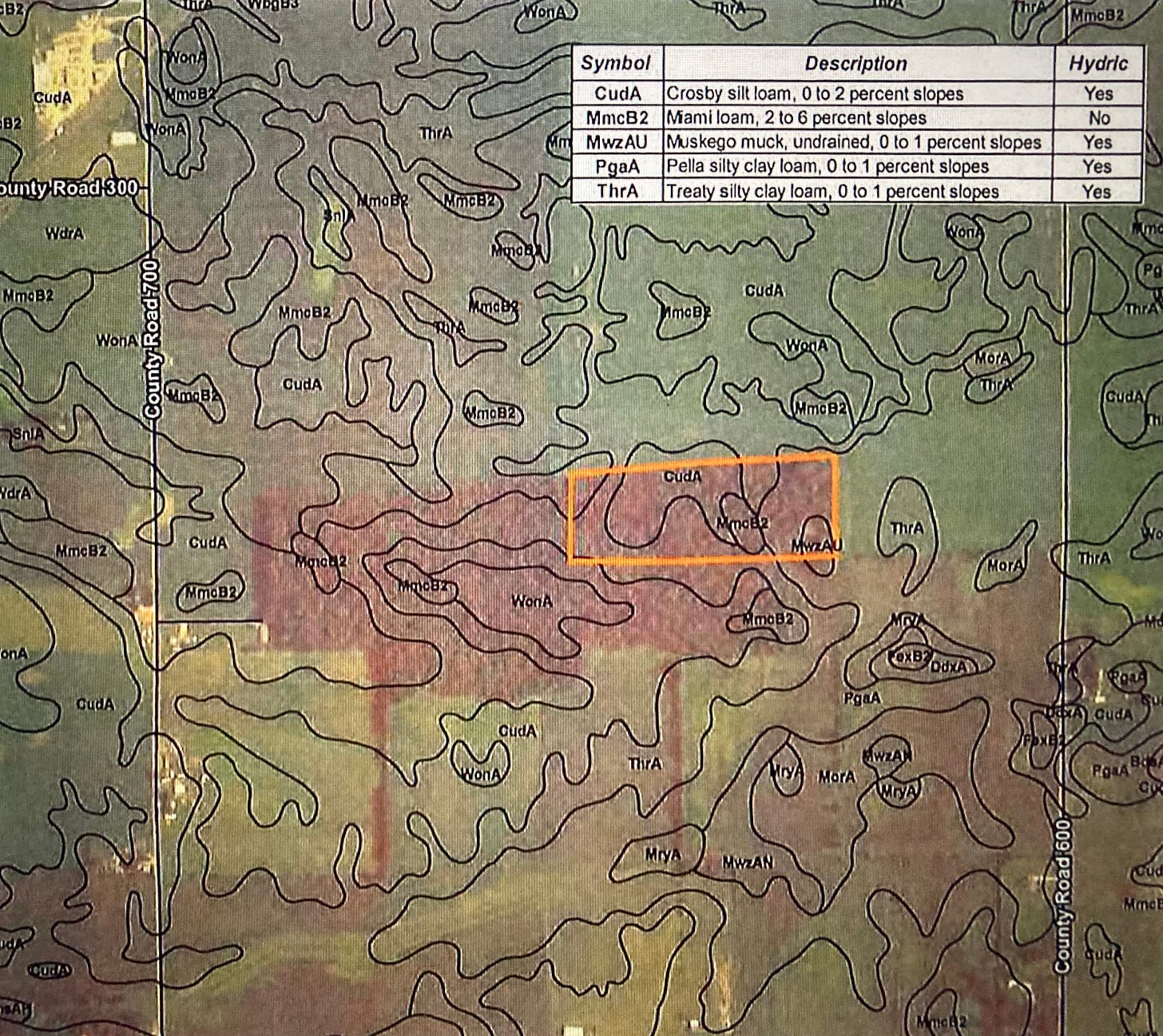

Meanwhile, in 2008, an environmental consultant hired by Yeley concluded that 11.82 acres of forested wetland had been present at the Yeley site, on Delaware County Road 600-W/Marsh Avenue south of Yorktown, before he had disturbed it.

The consultant’s report noted wetland plants and wetland soils on the property, along with “water standing in holes where trees had been removed,” and three data points where the soil was saturated within the root zone. But the report did not specifically note “site-wide wetland hydrology under normal circumstances.” Rather, flooding/soil saturation throughout the site under normal circumstances was “variable and had to be inferred,” the report said.

“We had a scientist review the original report, and we don’t think it was ever a wetland now,” Yeley’s attorney, Deveau, told me. “IDEM can’t infer hydrology (inundation/saturation) rather than take … samples and finding water … For it to be a wetland, even an isolated wetland, there has to be a lot of water. You can’t assume it.”

There was an undisturbed pond on the east side of the site, and the original wetland report assumed hydrology throughout the site based on the three data points taken in that saturated area, Deveau went on. “That inference was improper; you can’t establish a wetland exists over multiple acres by cherry picking/sampling a wet area and inferring the rest of the acreage also satisfies the hydrology requirements,” he said via email.

Hydrology, in this context, “is the fancy word for water, and lots of it,” the 7th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, Chicago, wrote in a 2019 decision, Boucher vs. United States Department of Agriculture.

In the 1990s, the now-late David Boucher cut down nine trees on his family farm in Hancock County, Indiana, which also happens to be Yeley’s home county. His purpose reportedly was to curb illegal dumping. The USDA disagreed, first with Boucher and then with his widow, Rita, about whether that modest tree removal converted several acres of wetlands into croplands, rendering the couple’s entire farm ineligible for USDA benefits under the federal “swampbuster” program.

The 7th Circuit reversed the federal trial court’s affirmation of the USDA’s final determination and remanded the case to the district court to enter judgment granting appropriate relief to Rita Boucher.

Determining the boundaries of a wetland requires evidence of the predominance of wetland vegetation, wetland soils, and signs of hydrology.

The Boucher court found that the USDA’s determination of wetlands was “arbitrary, capricious, abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accord with the law.”

In that case, federal agents did not look for primary or secondary indicators of wetland hydrology but instead assumed, incorrectly, that the site had been drained by the installation of drainage tile, and also assumed, again incorrectly, that the site was in a depression, the appellate court said.

Instead, an agent walked downgradient to an adjacent, supposedly comparable field and used observations from there to declare that the site in question had been a forested wetland converted to cropland. But the comparison site the agent walked to was “entirely unsuitable for comparison. It was an un-farmed area in a depression and was indisputably a wetland,” the court said.

To find primary indicators of hydrology sufficient to support a wetland, the federal agent could have looked for surface water, a high water table, or saturation, the court noted. Or, the agent could have dug a soil pit and observed the level at which water stood in the hole.

Absent at least one of the many primary indicators, federal agents could have looked for secondary indicators, such as certain vegetation, local soil survey hydrology data, or a depression, the court said.

Attorneys for Blinn and Yeley unsuccessfully tried to stop their cases from going to final hearings. Motions for summary judgment in their favor and against IDEM were denied.

Over the years, the number of legal arguments in the Yeley litigation keeps growing, and includes these two:

IDEM issued a violation letter to Yeley in 2008, then “apparently forgot about the site for many years,” not issuing a Notice of Violation (NOV) until 2014, long after the three-year statute of limitations had run, Yeley’s attorneys argued, adding: “Ever since, IDEM has been scrambling to resurrect dead claims.”

However, during a 2010 inspection, IDEM saw that the site was no longer being used for agriculture and was naturally restoring itself to a forested wetland. Then in 2013, responding to a complaint, IDEM observed soybean stubble and unharvested soybeans on the property. The 2014 NOV “survives for allegations arising from the … 2013 site inspection,” Judge Davidsen ruled.

Larry Yeley has denied that he owned the site in 2014, and he says that it was “an unidentified independent farmer” who harvested the soybeans observed by IDEM.

Both of those arguments were rejected by the judge, who cited county-government property-ownership records and wrote that it was unreasonable to assume that the Yeley family did not know the identity of the independent farmer, that the family was unaware that the site was being cultivated, and that the independent farmer committed trespass. Nor did the family try to interplead the independent farmer into the legal proceedings.

In 2018, Yeley hired an environmental consultant whose assessment of the site found no wetlands and who offered a professional opinion that “the site could not have restored itself as to constitute a forested wetland by 2013.”

IDEM argued that the site remained a wetland when cultivation began after 2010, that it is subject to regulation, and that cleared trees were dumped in the pond, contrary to law. The agency also argued that its characterization of the site as a wetland in 2007 remained relevant to its characterization when it was disturbed for crop cultivation as cited in 2014.

In denying the Yeley family’s motion for summary judgment, the judge determined that the family failed to meet its burden of showing that the site was not a wetland.

In moving the dispute along to a final hearing in May of this year, the judge wrote, “Genuine issues of material fact remain, as a matter of law, as to whether the site is a wetland subject to enforcement action.”

In the Blinn dispute, his attorneys accused IDEM of offering “inconsistent, malleable explanations for the flaw in its analysis;” of “repeated failures to follow its own procedures;” of “new, changing and contradictory arguments;” of “use of the wrong form;” of “use of the wrong vegetation calculation;” of “non-compliant choice of data points;” of “improper reliance on aerial imagery;” “and so on.”

“All of this, of course, is on top of the fact that the land is facially non-wetland, that federal regulators have examined the area and judged it to be non-wetland,” and that IDEM “admits that the land does not fit the governing wetlands definition in the Indiana code,” the attorneys argued.

Blinn’s lawyers, Christopher Bayh and Joel Bowers, also added the argument that IDEM’s actions amounted to an unconstitutional “taking” of his property without compensation.

IDEM responded that Blinn’s lawyers were just repeating many of the same arguments they made in their unsuccessful motion for summary judgment.

“Having no evidence to refute IDEM’s findings, respondent’s only option is to find inconsistencies between IDEM testimony that do not exist and to make arguments that are unsupported by the facts and law,” IDEM’s lawyer wrote. “In addition, respondent inappropriately attempts to preserve a takings claim for judicial review that was not raised on summary judgment or at the final hearing.”