Opioid addiction boomed in Muncie during Gas Boom

Was Dr. Anna Lemon Griffin an addict? Or victim of husband’s smear campaign?

MUNCIE — While doing research on a project called Notable Women of Muncie and Delaware County, Melissa Gentry found out about an opioid epidemic that swept the city during the Gas Boom era.

“When we started the … project, we wanted to make sure that we used the word ‘notable,’ so that we weren’t just studying women who had done something good, and so one of the first kind of complicated women that I researched was Dr. Anna Lemon-Griffin, and she was alleged to be a morphine addict,” said Gentry, the map collections supervisor at Ball State Universities Libraries.

Further investigation led Gentry to “a very dark side of history,” especially for women, during the unprecedented period of growth and prosperity that followed the discovery of natural gas here.

The opioid abuse outbreak starting in the 1880s resembled our current, still-evolving opioid crisis. Both lasted decades. Thirty-two Delaware County deaths were attributed to opioid overdoses in 2019.

A recent presentation by Gentry lacked opioid death statistics from the Gas Boom years. But it’s safe to conclude that Muncie was in dire straits then, too, because its newspapers were “littered with stories about women overdosing, either accidentally or otherwise,” on morphine.

Regular use of the pain reliever morphine — an opioid from which heroin is made — can lead to addiction.

“Advertisements for opiate-based, so-called patent medicines in Muncie newspapers promised relief from pain, nervousness and impotence … During the 1890s, the Sears and Roebuck catalog offered a syringe and a small amount of cocaine, morphine, or heroin for $1.50. Even babies and children were doped with opiate-based soothing syrups for coughs and for teething,” Gentry reported during a recent talk.

Like people overdosing today, many victims in the 1800s accidentally took too much morphine or mixed it with alcohol, Gentry said.

House calls for stomach pumps were common during this time in Muncie.

“Loved ones would discover a syringe and assume the motive was suicide, not realizing the victim was an addict reusing the same needle over and over,” Gentry said.

During a presentation titled, “Sinister Sisterhood: Opiate Addiction in Gas Boom-Era Muncie,” Gentry said the earliest morphine victim she found in Muncie newspapers was a 13-year-old from Winchester who overdosed in 1879.

Other examples:

One addict was taken to a Walnut Street sanitarium by her husband. When the woman lacked withdrawal symptoms after several days, it was discovered that she had hidden six weeks’ worth of morphine in her thick hair.

Daisy Thomas, 17, overdosed on morphine after an argument with her suitor, fighting off her sister with a syringe.

Stella Stillwater, thought to be near death after she had “filled herself chock full of morphine,” was just imbibing for fun. She was surrounded by syringes and beer.

In 1891, two Muncie women, Lillie Rowe and Mamie Fisher, aka Anna Oakley, who were arrested for prostitution, were able to stop at the Star Drug Store on their way to jail and purchase cigarettes and morphine. In their cell, each wrote a goodbye letter and then took half of the morphine in an apparent but unsuccessful suicide attempt.

In 1906, Miss May Holder, a member of a prominent family, was arrested for shoplifting at a downtown Muncie store. Eight years earlier, her baby had died, and her husband had divorced her. A doctor gave her morphine. “Her condition was extremely serious and it was necessary for her to keep continually increasing the dose and now she takes enough at one dose to kill several men.”

A doctor prescribing morphine to ease emotional anguish led Holder and any number of Muncie women down this road of addiction and subsequently crime or even death, Gentry reported.

While morphine and heroin were legal at the time, it was considered inappropriate for members of reform movements like suffrage and temperance to use alcohol, Gentry said. So doctors prescribed morphine for nervous conditions, headaches, menstrual cramps and even morning sickness.

Many reformers, artists and writers — including Louisa May Alcott (“Little Women,” “Little Men”) and social reformer Jane Addams — were users.

Once a woman started using morphine advised by her doctor, she could then buy as much as she wanted at the drugstore, Gentry said. Even young teenagers could buy it. Drugs were unregulated.

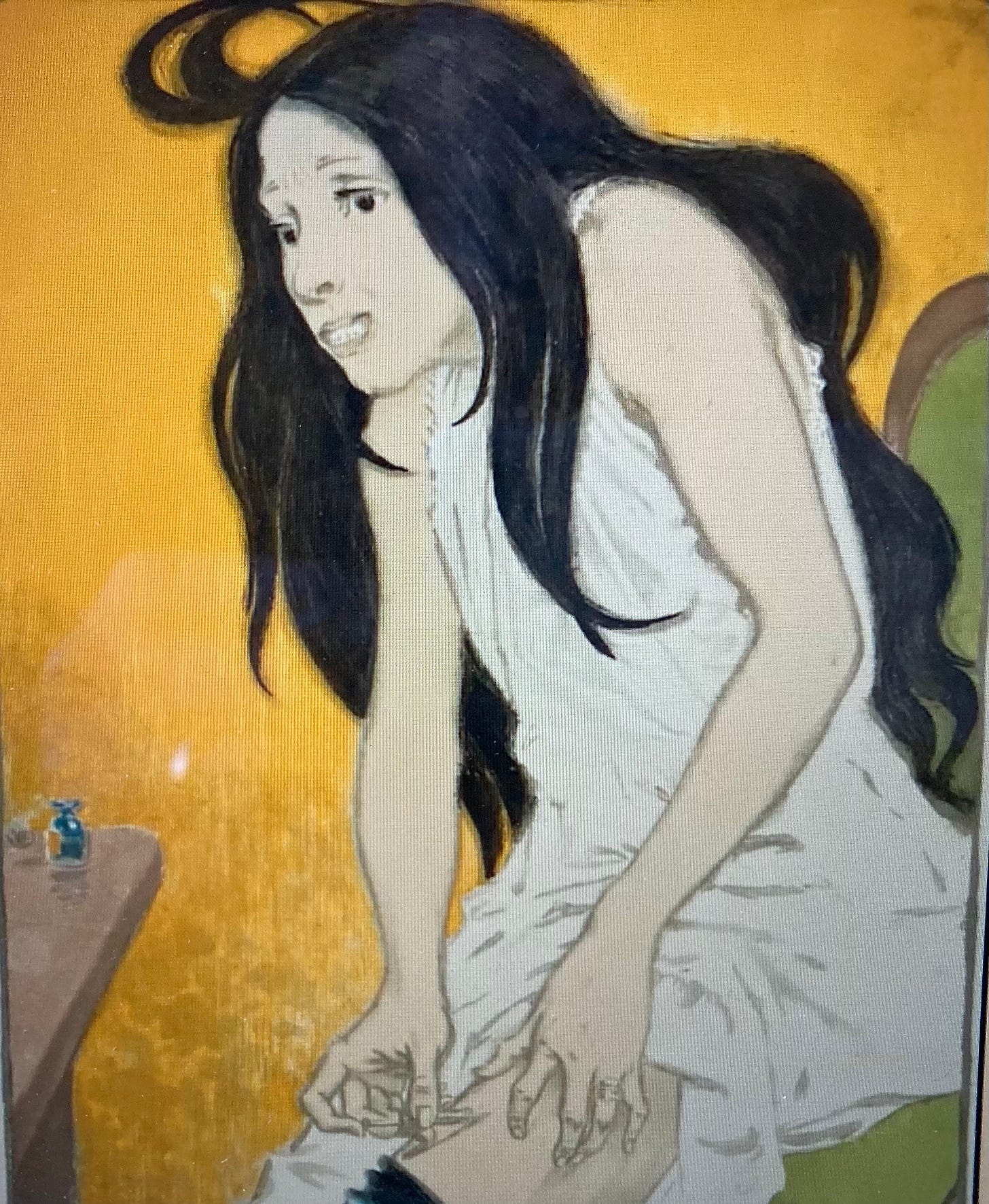

One of the first Notable Women of Muncie Gentry encountered during her research was surgeon Anna Lemon-Griffin, a respected member of the local medical society. One of her offices, at 20th Century Flats, on Jefferson Street downtown, was saved from the wrecking ball in 2012 and is now an apartment building.

In 1903, after eight years of marriage, Dr. Griffin filed for divorce, charging her husband, William Griffin, with neglect, cruelty, and adultery, Gentry said. A court denied the divorce.

Then, in 1905, William filed for divorce, claiming that his wife had threatened to chloroform and operate on him during his sleep — potentially killing, maiming or torturing him with her surgical instruments and skills.

During a trial, William’s daughter, Anna’s step-daughter, testified that Dr. Griffin once had entered William’s room and threatened him: “Now blank blank you, I have you and I will get you this time.”

Newspapers around the country picked up the scandalous story.

William testified that Anna had been addicted to morphine for at least the last five years. She did not appear in court to defend herself, and the divorce was granted. Her reputation as a doctor was destroyed.

Gentry said Anna was detained by the police in Kokomo in 1906 after she could not pay the bill for a boarding house. Dr. Griffin told police that her husband had been stalking her and that she was afraid. “There has not been an hour in the last five years that I have been sure someone was not spying on me...” reducing “me to the nervous wreck that you see,” she was quoted as saying.

Authorities sent her to the state hospital in Logansport, where her condition was reported in the 1906 American Medical Association bulletin as “temporarily deranged.”

“The truth is muddy in this situation,” Gentry said. “We’ve all seen this movie before, where in a ‘he said/she said’ account, the man’s word is considered true and the woman is considered crazy. So we can’t be certain if Dr. Anna Lemon-Griffin was, in fact, addicted to morphine. But it is entirely possible. It’s possible because during this opiate epidemic, doctors and women were the main addicts.”

After the talk, Gentry told me, “When I looked into it, I realized that, I think they said 60% of opium addicts at that time were women. And the other major addicts were doctors. And the doctors were the ones that were prescribing to women, and the doctors who were prescribing the most were the ones using the most. I thought that was kind of an interesting story.”

After the turn of the century, the demographics of the drug addict were changing to include more young men and African Americans. Coincidentally or not, that’s when laws changed, Gentry said.

By 1905, Congress was enacting legislation that regulated or banned opiates.

“Most of the so-called patent drugs were flushed out of the market due to these new regulations especially related to illicit ingredients, but some products like Coca Cola, made with cocaine, survived,” Gentry concluded. “And sadly, so too has addiction. The current opioid crisis reminds how history repeating itself can be sinister and deadly.”